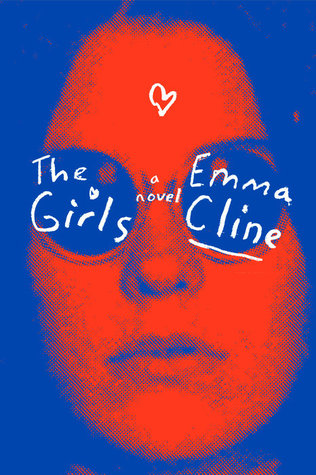

Genre: Literary Fiction

I looked up because of the laughter, and kept looking because of the girls.

I noticed their hair first, long and uncombed. Then their jewellery catching the sun. The three of them were far enough away that I only saw the periphery of their features, but it didn’t matter—I knew they were different from everyone else in the park. … These long-haired girls seemed to glide above all that was happening around them, tragic and separate. Like royalty in exile.

Most readers have a pet genre. Dystopian YA. Police procedurals. Scandi crime. Gothic romance. Epic fantasy. My favourite? Books that have been likened to Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992). That may sound oddly specific, but there are a bunch of them out there. Personal favourites include: Marisha Pessl’s Special Topics in Calamity Physics (2006), Curtis Sittenfeld’s Prep (2005), Lev Grossman’s The Magicians (2009), Jennifer McMahon’s Dismantled (2009), Lucie Whitehouse’s The House at Midnight (2008), Ivo Stourton’s The Night Climbers (2007), and here in Australia, Sonya Hartnett’s All My Dangerous Friends (1998) and Emily Bitto’s Stella Prize-winning The Strays (2014). There are dozens more, too, of varying distinction. And it doesn’t matter how many I read, I never tire of them, so when I heard Emma Cline’s debut novel, The Girls (Random House, Jun. 2016), being hailed as ‘the next The Secret History‘, it went straight to the top of my reading pile.

The Girls takes inspiration from the Manson Family and their crimes and seeks to understand the appeal of such a group for a teenage girl. In 1969, fourteen-year-old Evie is self-conscious, disillusioned and eager for an extraordinary life. She longs to be noticed. To belong. To be loved.

Every day after school, we’d click seamlessly into the familiar track of the afternoons. Waste the hours at some industrious task: following Vidal Sassoon’s suggestions for raw egg smoothies to strengthen hair or picking at blackheads with the tip of a sterilised sewing needle. The constant project of our girl selves seeming to require odd and precise attentions.

It was an age when I’d immediately scan and rank other girls, keeping up a constant tally of how I fell short.

Enter Suzanne. Nineteen. Free-spirited. Wild. At least on the surface. And Evie can’t believe her luck when Suzanne accepts her as a friend and invites her to hang out at the ranch outside of town where a so-called visionary and soon-to-be pop star named Russell is experimenting with a new way of life.

There was an air of otherworldliness hovering around her, a dirty smock dress barely covering her ass. She was flanked by a skinny redhead and an older girl, dressed with the same shabby afterthought. As if dredged from a lake. … They were messing with an uneasy threshold, prettiness and ugliness at the same time, and a ripple of awareness followed them through the park.

However, by summer’s end, Suzanne and her friends will have committed an unspeakable crime, leaving four people, including a young boy, dead. They’ll be infamous. Talked about for decades to come. While Evie will remain unremarkable. Caught between jobs in late middle-age, she finds herself looking back, wondering how different her life, and perhaps her friends’ lives might have turned out if she’d been with them the night of the murders, and whether she would have tried to stop them or readily played a role in the violence.

If you’ve read The Secret History, you’ll no doubt find the parallels difficult to ignore. Both novels focus on a young protagonist seeking entry to a false paradise that promises a heightened way of life but delivers only destruction and death. They are stories of desire, yearning and obsession that explore our fundamental need to belong. And they spotlight dissatisfied, unglamorous people fighting to reshape their identities, and, in doing so, place their faith in false idols. There is something shared in their narrative style too. Both Tartt and Cline favour vivid and richly detailed prose; their narrators are nostalgic and seek to enchant, to defend their friends’ crimes and, by extension, themselves. Evie presents her friends’ crime like a sacred object, carefully unwrapping it from folds of tissue paper and holding it up to show it in its most flattering light:

I had imagined that night so often. The dark mountain road, the sunless sea. A woman felled on the night lawn. And though the details had receded over the years, grown their second and third skins, when I heard the lock jamming open near midnight, it was my first thought.

Christ, ‘felled on the night lawn’? Is she a Romantic poet? It’s eerie. Chilling. And unmistakably similar to the way Richard Papen recalls Bunny’s murder in Tartt’s prologue:

Now that the researchers have departed, and life has grown quiet around me, I have come to realise that while for years I might have imagined myself to be somewhere else, in reality I have been there all the time: up at the top by the muddy wheel-ruts in the new grass, where the sky is dark over the shivering apple blossoms and the first chill of the snow that will fall that night is already in the air.

However, there are key stylistic and thematic differences. The Secret History is a story about repression and restraint and denial, with the members of the Greek class forced to increasingly desperate acts to hide not only their crimes but also their true characters and the lives they left behind when they enrolled at Hampden College. It’s all dark, muted tones and hushed conversations. Between the lines, it’s a very different story, but on the surface, it’s controlled. Polished. Masculine. Or, at least, the (almost exclusively male) cast try to live up to an ancient idea of masculinity: ‘Duty. Piety. Loyalty. Sacrifice.’ Values an army can march by. The sex, the violence, the blemishes are glossed over or else occur off-page. The Girls, by contrast, is garish, vivacious and wild. Cline tears away the polished ideal that her young women read about in their magazines and luxuriates in the imperfections they have been conditioned to hide: their sexual curiosity and hunger for power and status, their reeking bodies, unwashed hair and ratty clothes. ‘Even the pimples I’d seen on her jaw seemed obliquely beautiful, the rosy flame an inner excess made visible.’ She lays bare every insecurity and desperate thought.

So much of desire at that age, was a willful act. Trying so hard to slur the rough, disappointing edges of boys into the shape of someone we could love. We spoke of our need for them with rote familiar words, like we were reading lines from a play. Later I would see this: how impersonal and grasping our love was, pinging around the universe, hoping for a host to give form to our wishes.

Girls are the only ones who can really give each other close attention, the kind we equate with being loved. They noticed what we want noticed.

For me, The Girls embraces the ugliness and uncertainty of female adolescence with the unflinching honesty that few books seem to muster (in that respect, it’s a sister to Sittenfeld’s aforementioned Prep and M. J. Hyland’s How the Light Gets In (2003)). It makes for both highly unsettling and deeply comforting reading. On the one hand, I was horrified to find myself relating so strongly to Evie, but on the other, it was reassuring to read a story where a young girl is allowed to be vain, self-centered, cruel, ambitious and insecure without also becoming the villain. And I think that’s a big part of the book’s success.

That, and the fact that Evie doesn’t join a cult and do a whole lot of stoopid stuff to get close to Russell, which, with him being the group’s leader, would be the most logical explanation. Instead, it’s Suzanne who entices her to the ranch. Suzanne functions as a kind of anti-hero—a striking and extreme inversion of the girls who smile from the pages of teen magazines.

The girl [Suzanne] wasn’t beautiful, I realised, seeing her again. It was something else. Like pictures I had seen of the actor John Huston’s daughter. her face could have been an error, but some other process was at work. It was better than beauty.

Since I’d met Suzanne, my life had come into sharp, mysterious relief, revealing a world beyond the known world, the hidden passage behind the bookcase.

By turns, Suzanne cajoles and coerces Evie to steal, to lie, to take drugs and have sex. For Evie, Suzanne embodies a more pure and uninhibited way of life. But to the reader, she’s a tragic figure, much like Henry in The Secret History. We learn very little that’s reliable about her past, but there’s a sense that it’s been marked by trauma. Her beauty lies in the promise of its destruction, and her involvement in the murders is inevitable. Necessary.

Most of us would like to believe that we are ‘good’ people. Incorruptible in the ways that matter. What makes The Girls both a gripping and terrifying read is the way Cline so convincingly proves that this is not the case. For all the beauty magazines and self-help books we read, and for all our work at crafting a stable, civilised existence, we are not so very far removed from our basest desires. For women in particular, who are constantly monitored, critiqued and scolded for failing to meet impossible standards, there is something incredibly exhilarating and cathartic in watching Evie abandon all that conditioning to chase after the thing she most desperately wants, stopping a mere half-step shy of her own destruction and wondering for the rest of her life if it wouldn’t have been better just to keep going.

The group’s symbol is a heart, innocent and innocuous until the girls paint it in blood at the scene of the crime, transforming it into something terrifying, raw and powerful. Could there be a more fitting symbol for girlhood? Cline does the same thing with her young characters and it makes for thrilling reading.

See The Girls on Goodreads and purchase through Booktopia, Amazon and Book Depository.

Thank you to Random House for providing a copy of The Girls in exchange for an honest review.

Thanks also to Grammarly for picking up seven critical issues and twenty-four advanced issues in my draft of this review. If, like me, you have trouble with typos, do give Grammarly a go!

Like what you see? Keep in touch:

|

|

|

|